Preach the Word – The Gospels: The Center of the Gospel

Preaching on the First or Second Reading with the Day’s Gospel in Mind

1 – The Gospels: The Center of the Gospel

The gospel is the good news that God forgives sins and saves sinners. This is good news because without this news the news is bad: God condemns sin and destroys sinners. Lutheran preachers make the gospel the priority of their preaching because the good news is the best news a sinner could ever hear.

The Bible communicates the good news in a variety of pictures. The good news is that God and sinners are reconciled; sinners are at one with God. The good news is that sinners are redeemed; they are bought back from the slavery of sin and the dungeon of destruction and restored as God’s children. The good news is that sinners are justified; God declares that sinners have a new status in his sight, a status in which he sees them as holy and blameless. Lutheran preachers use these and dozens of other Bible pictures to announce the good news.

The gospel is more than news, however. It is also power. In a way that we preachers cannot grasp, the Holy Spirit employs the good news to lead sinners to believe the good news. By the power of the gospel sinners come to trust what they have no right or reason to believe. As the gospel invades their minds and hearts, believers begin to understand the depth of God’s love. They gain courage in trouble, strength in weakness, confidence in prayer, joy in obedience, and hope for a life with God that never ends. As they preach the good news, Lutheran preachers provide the Spirit an opportunity to change the lives of sinners as he wishes and wills.

Lutheran preachers also preach the bad news, the law. The bad news clarifies the realities of sin. The law is not what the sinner wants, but what God wills. Obedience to the law is not a maybe but a must. Condemnation for sin is not a possibility but an absolute. The law does not coddle but warns. Without the preaching of the law, the gospel is ho hum and so what. The gospel will not be sweet until the law becomes putrid in the sinner’s soul.

Law and gospel. These two teachings, the most important truths of the Bible, must form the heart and core of the preacher’s sermon. Jesus, Paul, and Luther exemplified law and gospel preaching. C.F.W. Walther wrote a book about it.1 The absolute goal of Lutheran preaching is to announce and apply the law and let it do its work and to announce and apply the gospel and let the Spirit do his work. No greater epitaph can placed on a preacher’s headstone than this: He preached the law and the gospel.

The center of the gospel is Jesus, the Son of God from all eternity and then, in time, even this time, the son of Mary. The righteous God cannot forgive, reconcile, redeem, or justify without Jesus. The God-man stands at center of the Bible: everything before him foretold his coming; everything after him explained his coming. What the serpent first heard after Eden, Moses, David, and the prophets anticipated and announced. The Alpha and the Omega John saw in his vision of the future is he who walked with the apostles in time. Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever.

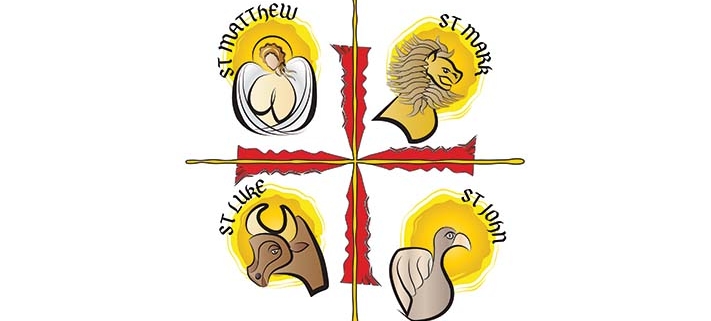

So what did Jesus do and what did Jesus say that qualifies him to be center of the Scriptures and the central character of human history? The Spirit tells us this in the Gospels. What the apostles proclaimed in the days following Pentecost, four men, guided by the Spirit, wrote down some years later. Each man’s central character was Jesus, although each man, guided by the Spirit, told the story from a different perspective. Together these four, two apostles and two apostolic co-workers, presented the life and times of Jesus so that we are able to see how reconciliation, atonement, redemption, and justification were achieved. They present to us the Savior in his dual nature as divine and human. They assert that he was the one God had promised in the past. They point out his perfect obedience to the law in the place of sinners. They describe his desired use of baptism and his institution of the holy meal. With extraordinary detail they note the innocence of his suffering and the stark reality of his death as payment for sin. All proclaim his resurrection and the final days of his time on earth. Besides recording his deeds, each Gospel writer added thousands of words from the Savior’s own lips which announced the realities of sin and the good news of forgiveness. John alludes to all these words and works of Jesus when he writes at the end of his Gospel: “Jesus performed many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not recorded in this book. But these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name” (John 20:30-31).

Of course, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are not the only Bible writers who knew the Savior’s words and works. Moses promised a prophet, David could envision a king, Isaiah described the suffering servant and his ultimate sacrifice. Zechariah could see the donkey, Micah knew about Bethlehem, and Malachi saw the Baptizer, but everything they saw and heard described the God-man who would work and teach in Palestine for 33 years. Peter proclaimed the universality of his Savior’s kingdom, Paul explained justification by grace and faith alone, and John described love as the essential feature of fellowship with God, but they all based their words and their faith on what Jesus said and did. And what Jesus said and did is recorded in the Gospels.

Much of Christian and Lutheran preaching over the centuries has proclaimed the gospel on the basis of accounts from the Gospels.

It does not surprise, therefore, that much of Christian and Lutheran preaching over the centuries has proclaimed the gospel on the basis of accounts from the Gospels. The first Christians replaced the betrayer with a man who had been with the apostles “the whole time the Lord Jesus was living among us, beginning from John’s baptism to the time when Jesus was taken up from us. For one of these must become a witness with us of his resurrection” (Acts 1:21-22). The same believers “devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching” (Acts 2:42). Peter’s sermons after Pentecost inevitably led to the words and works of Jesus; Paul’s sermons do, too (the notable exception being the Areopagus mission sermon). The early church fathers, including Ambrose and Augustine, regularly preached on the Gospel appointed for Sundays and the great festivals.2 Almost all of Luther’s published sermons, at least in the American Edition, are based on Gospel texts, although much of his preaching took place within the context of the Sunday Gottesdienst where it was expected that the historic Gospel would serve as the day’s text. This expectation remained in place at least in Europe until 19th century, often dictated by provincial consistories. Good Lutheran preachers even in WELS seem not to have hesitated to preach on the historic Gospel every Sunday. One gets the impression from personal conversations that many of today’s WELS preachers still preach on the appointed Gospel texts more often than on Old Testament and Epistle selections.

For hundreds of years, the choice of the Gospel text was as much pragmatic as it was principled. At least on Sundays, the historic Epistle was the only other possibility.3 In an effort to relieve some of the monotony, Lutheran churchmen offered alternate series of preaching texts with the claim, however, that these were intended to match the historic Gospels. Old Testament texts chosen to accompany the historic Epistles and Gospels were generally buried in small print (cf. The Lutheran Hymnal, pp. 159-161) or reference works (cf. The Lutheran Liturgy, p. 459 ff.4). In most cases, Old Testament texts were reserved for occasional services.

The introduction of the three-year series, offered by Roman Catholics in 1967 and then in revision by the Inter-Lutheran Commission on Worship in 1973, suggested a new pattern. The liturgical rites created in that era included three readings on Sunday, one from the Old Testament, a second from one of the Epistles (or Acts during the Easter Season), and the third from one of the Gospels. Perhaps with more intensity than previously, our professors encouraged their students to rotate the three texts in preaching. Rotate we did in a variety of ways. The most efficient rotators preached equally on all three selections, e.g., Old Testament texts in Advent, Epistles over Christmas, Gospels during Epiphany, etc. Others followed the same sequence Sunday by Sunday. In many cases the believers in the pew heard as many sermons based on prophetic texts and teaching texts as sermons based on the words and works of Jesus.

Of course, there was value in this. Preachers were able to proclaim law and gospel to their hearers by means of Old Testament history and prophecies. They explained Old Testament history and its messianic implications. Preachers used Epistle texts to detail theological intricacies and applied them to the Christian life. The lectio continua nature of the initial set of Epistles enabled preachers to work through a single letter over a series of Sundays and highlight its content as they might do in a Bible class. The selected Gospels offered more of the words and works of Christ than the historic series had.

Much of preaching was unaffected by this change in mood. Preachers still based their text studies on the original languages and relied on the historical-grammatical method of textual interpretation as they had been taught at the seminary. The preacher proclaimed law and gospel through Isaiah’s pen and Paul’s writing as well as he had when preaching the words and works of Jesus. Preaching remained expositional and propositional as it had always been. In some cases, however, what came to be missing were the words and works of Jesus. Not on the festivals, of course. One can hardly preach on Jonah’s prayer from Jonah 2 on Easter without a focus on the resurrected Christ. The preacher simply can’t focus on the messenger who brought good news to Jerusalem (Isaiah 52) on Christmas Day without including the messenger who is Christ. But other Sundays don’t force such a connection. Ruth’s decision to follow Naomi’s God doesn’t require comparison with the leper’s decision return to give thanks and confess his faith. One can preach on Paul’s storm experience in Acts 27 without mentioning the storm on the Sea of Galilee which Jesus calmed.

Perhaps with more intensity than previously, our professors encouraged their students to rotate the three texts in preaching.

As the years passed as a regular preacher and as I taught seminary Middlers how to preach on Old Testament and Epistle texts, I began to wonder if it is possible to preach on the First or Second Readings assigned to a Sunday and connect them to the Gospels appointed for the day. In other words, can the preacher remain faithful to legitimate homiletical principles of exposition and proposition and yet enable the text to focus also on the words and works of Jesus? When the three readings are carefully chosen, can the preacher find a legitimate connection between the First or Second Reading and the day’s Gospel and can he include both the focus of the preaching text and the day’s Gospel in the sermon? I have no desire to compromise the truths or the settings of the readings; I do sense a desire to connect them to the words and works of Jesus. As an every-Sunday preacher again, I have opportunities to test this concept.

Can the preacher find a legitimate connection between the First or Second Reading and the day’s Gospel and can he include both the focus of the preaching text and the day’s Gospel in the sermon?

The Preach the Word articles which follow this introduction will explore this idea. Sections of a sermon based on 1 Kings 3:5-12, appointed to accompany the Gospel from Matthew 13:44-52 (Proper 12 of Year A in the new hymnal lectionary), provide an example of what this series means to explore.

Written by James Tiefel

Prof. Tiefel, now Pastor Tiefel, serves two small congregations in Mequon, WI, in semi-retirement. Over a 35-year career at Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary he taught classes in worship and preaching. As an every-Sunday preacher once again, he is able to combine many of the concepts he taught in the classroom with practical experience.

I want to tell you a story you’ve all heard before. There was this guy and he was out for a walk, just looking around at the trees and the flowers and the big blue sky. All of the sudden he tripped and almost fell on his face. He figured it was a root or a stone, but when he looked it was a box, an old, beat up wooden box. He bent down and opened the cover—the lock had rusted away a long ago—and what he saw he couldn’t believe. He’d been in plenty of jewelry stores, but he’d never seen anything like this. What to do. He couldn’t offer to buy the stuff; it was obviously priceless. He wasn’t going to steal it, although the box was way too old to belong to the young farmer who owned the land. He was going to do this legally. He raced into town, got together every dime and dollar he owned, made an offer, bought the field and he got the treasure. You know why. The treasure mattered. It changed his life.

Here’s another story; you heard this one, too. He was a purveyor of pearls, those creamy white oval stones you find inside oyster shells. This guy knew pearls backwards and forwards; he knew the difference between fake and genuine and even between low quality and high quality. So one day, he found a pearl like he had never seen before. It had uncommon luster, brilliant color, and perfect shape. The price tag was outlandish, but he got together every dime and dollar he owned, made an offer, and he got the pearl. And you know why. The pearl mattered. It changed his life.

You know both of these stories because you heard Jesus tell them in today’s Gospel. The parable of the hidden treasure and the pearl of great price are two of the seven parables Jesus told his followers in one fairly long sermon. Jesus made the same simple point in both parables: Search for what really matters in life and then do what needs to be done to own it and keep it.

So what really matters in life? Well, we all know the answer. We’re Christians and faith tells us what matters. The trouble is that our brains and our emotions don’t always follow faith. The line between what matters and what doesn’t matter gets blurred. Health matters, relaxation matters, possessions matter, education matters. And even if we know in our hearts what really matters, we struggle to pay the price to gain it and guard it.

The man in the field, the man in the jewelry store, and a man in Gibeon all teach us the same truth. You know the man in Gibeon, too, because you heard about him in the First Reading. The man is Solomon, the king of Israel, and his story isn’t a parable. It’s an actual event that took place at the very beginning of his reign. The story begins when God comes to the new king and says, Ask for whatever you want me to give you. Solomon’s response reminds us of this truth:

What We Want Is What Matters

1. Solomon almost didn’t get to be king. Even before his father David died there were palace intrigues and military coups that could have kept Solomon off the throne and maybe even left him dead. But Solomon was David’s choice and even more he was God’s choice and that settled it. Solomon proved himself the be the right choice. He showed his love for the Lord by following David’s instructions and by honoring God with his obedience and respect.

But he was young, probably only 20, when he became king. He had almost no experience. The nation of Israel was an emerging empire and surrounded by jealous monarchies. And ruling over 5,000,000 people—about the population of Wisconsin—who were notorious for being surly and stubborn would have intimidated anyone. So when the Lord invited Solomon to ask for whatever he wanted, this is what Solomon said, Now, Lord my God, you have made your servant king in place of my father David. But I am only a little child and do not know how to carry out my duties. Your servant is here among the people you have chosen, a great people, too numerous to count or number. So give your servant a discerning heart to govern your people and to distinguish between right and wrong. For who is able to govern this great people of yours?

1 C.F.W. Walther, The Proper Distinction between Law and Gospel, W.H.T. Dau, translator (St. Louis: Concordia, 1927).

2 M. F. Toal, The Sunday Sermons of the Great Fathers, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000).

3 A stack of sermon outlines created by noted WELS pastor Carl Gausewitz indicates Gausewitz preached on the historic Epistles and Gospels throughout the entire year in alternating years, apparently with the same outline.

4 Luther Reed’s classic study of Lutheran worship was published by Fortress Press, Philadelphia, in 1947.

WORSHIP

Learn about how WELS is assisting congregations by encouraging worship that glorifies God and proclaims Christ’s love.

GIVE A GIFT

WELS Commission on Worship provides resources for individuals and families nationwide. Consider supporting these ministries with your prayers and gifts.

[fbcomments num=”5″]