Wisdom from Wittenberg – Part 2

Wisdom from Wittenberg – Part 2

Martin Luther’s Pastoral and Practical Revisions of Worship

Creativity is careful to honor the arts.

Though Luther considered Karlstadt’s experiments to be troubling (see part 1), he realized that they weren’t unique. By 1524, worship experiments were underway all over Germany, many initiated by reformers who were becoming increasingly estranged from Luther in the wake of Karlstadt. In Allstedt, Thomas Müntzer—in addition to propagating Anabaptism—was composing a vernacular service1 and vernacular translations of ancient hymns. Nearer-by in Zwickau, Nicolas Hausmann, the very pastor to whom Luther had dedicated the Formula Missae, sent Luther in 1525 some new German masses for critique.2

Luther felt that they all suffered from the same problem: the old tunes didn’t fit the translated texts.3 While pragmatic, these mass experiments lacked artistry. While aiming at re-formation of the service, they were nothing more than “loosely connected amalgams of prayer, preaching, and singing.”4

Luther’s solution, a German service for Wittenberg, aimed for a higher standard. To achieve this, he enlisted professional help. In October of 1525 as the Deutsche Messe texts and tunes were nearing completion, Luther requested the Elector to dispatch court composer Conrad Rupsch and his protégé Johann Walter to collaborate with him. For three weeks, they scrutinized texts and tunes.5 By mid-November, completed drafts were sent to Torgau for electoral approval. The texts were clean, the notes well-matched and well-tuned. Whether or not he intended it, Luther was putting church musicians on notice: if something is worth doing, it’s worth doing right.

Luther also put preachers on notice. “I think that if we had a German postil (a biblical commentary in sermon-form) for the entire year, it would be best to appoint the sermon for the day to be read entirely or in part out of the book—and not just for the benefit of those preachers who can do nothing better. …otherwise we will reach the point where everyone will preach his own ideas and instead of the Gospel we will have more sermons about ‘blue ducks.’”6

Luther’s critique can seem confusing until we realize the sad state of preaching in and around Wittenberg. Preachers were either so clumsy in explaining a text or so eager to offer their own ideas that sermons spun off into nonsense. Luther’s sharp critique boils down to this: those who can’t appreciate the art of preaching ought to read and imitate someone who can.

Luther’s expectation for excellence in artistic craft appeared throughout the Deutsche Messe and its accompanying resources. When he translated ancient prayers,7 he did so in ways that recognized and appreciated their ancient form. When he enlisted the most respected poets to translate old hymn texts and compose new ones,8 he expected clear and elegant language. When he commended pastors to chant the lessons, he gave them specific instructions to ensure it was done well.

Why was Luther so adamant about art forms? The preaching problem is illustrative. When a preacher bungles a text or, worse, ruminates on something foreign to the text, what is happening to the gospel message? When a poet bruises the language or a composer mis-matches the tune, a disservice to the gospel is taking place. Luther’s concern for the arts in worship is not art for art’s sake. “In Luther’s view, music in the church functions as viva vox evangelii.” How do music and art carry out this task? “By faithfully reflecting in its own terms the honesty, integrity, truthfulness, and winsomeness of the gospel.”9 Luther’s pastoral heart expected any tool used to express the gospel to be expertly handled and any tune accompanying the gospel to be expertly crafted.

Luther’s passion for the arts is an extension of his foundational principle. Once the creative arts have been placed into the service of the gospel, it follows that our creative impulses would also be placed into the service of the arts. Luther was acquainted with prominent musicians who were working to define and explore new musical techniques and innovations. Luther’s humanist contemporaries used the term ars (“art”) to describe the rules and techniques that could be taught and learned, and the term ingenium (“genius”) to describe the musician’s original and creative impulses. Both concepts are not only important to music, but required.“Ars without ingenium is insufficient, and ingenium alone is despicable, since it places itself above all musical order.”10 There are thus two temptations to avoid: the first, to basically reproduce artforms with no passion or creativity; the second, to simply ‘do our own thing,’ preferring our own genius rather than realizing the rules and working within the limits of the art.

Luther might unleash his good-natured wit on us against these two temptations: “Your passion for the past is commendable. And your plan to preach like I preach is well-intentioned. But art without genius won’t do!” Alternatively: “Your genius is a gift of God. Your next sermon series might be a creative gem. And your new ideas for adapting a service may be great. But have you taken the time to appreciate the form of art that you are improving or replacing? Or are you simply offering an “ape-like imitation?”11

Luther’s carefully crafted service is a reminder that the pursuit of excellence through artistic standard and craft leads each individual (preacher, player, planner, and more) to appreciate their role as a steward of God’s creative gifts and to acknowledge that God has blessed us with far more than our own cherished “tavern tunes,” “tin whistles”12 and “blue ducks.”

Creativity is careful to serve the community.

Hausmann’s letter to Luther wasn’t the last request for Luther’s pastoral advice. Luther became aware of a troubling situation in far-off Livonia (present-day Estonia). This time, it had nothing to with artistic integrity. A new fanatical preacher, Melchior Hoffmann, was causing the same kind of upheaval that Karlstadt had started in Wittenberg three years earlier. Hoffmann was soon toe-to-toe with the disgruntled church council who sent him to Wittenberg for advice from Luther. They also sent a letter to Luther asking, in effect: “Tell us what we should do!”

We can only speculate about what they expected to hear. On the one hand, Luther could have prescribed a precise format of what was appropriate and what not.13 On the other hand, Luther could allow every congregation to determine its own way,14 based on the consensus of the pastor, the council, and the people.

But Luther offered neither of those solutions. Instead, he wrote, “I pray all of you, my dear sirs, let each one surrender his own opinions and get together in a friendly way and come to a common decision about these external matters, so that there will be one uniform practice throughout your district instead of disorder—one thing being done here and another there—lest the common people get confused and discouraged.”15 In other words, ‘do what seems best to you; but please, do it together with your fellow churches.’

Luther offered pastoral latitude within limits.

This thread of regionally-determined liturgical unity rather than congregational independence is woven into the fabric of the Deutsche Messe. “I do not propose that all of Germany should uniformly follow our Wittenberg order…. But it would be well if the service in every principality would be held in the same manner and if the order observed in a given city would also be followed by the surrounding towns and villages.”16 Luther then also offered pastoral latitude within limits: “It shall be understood that such communion, hymns, readings, and preaching are under the responsibility of the pastor, and may be increased or reduced according to the circumstances of the day.”17 Pastors were free to make various choices within a liturgical framework shared among churches in the district.

Luther was defending pastoral and congregational freedom while at the same time advocating that the freedom of a particular pastor or congregation be limited by love which serves their neighbor. The freedom of the individual submits in love to the needs of the neighbor. In this way, congregations would avoid falling into the ditch of legalism while at the same time avoiding the ditch of faddism or creativity-run-amok.

So much for the principle. But how could such a balance of freedom and love be struck, especially among German people known for their streak of independence?18 Luther’s practical solution was peer review. Anything newly created for worship should, as a matter of course, undergo careful scrutiny. Luther then offered as first specimens his own paraphrase of the Lord’s Prayer and his exhortation to the Lord’s Supper. “[How] this paraphrase should be read, I leave to everyone’s judgment…. I would, however, like to ask that [it] follow a prescribed wording … for the sake of ordinary people. We cannot have it done one way today, and tomorrow another different way, letting everybody parade their talents and confuse people so that they can neither learn nor retain anything.”19

Luther’s practical solution was a peer review.

Incidentally, neither of Luther’s specimens would survive. In Wittenberg’s first church order (1533), neither idea was included. Pastors and people simply returned to the familiar patterns of the Lord’s Prayer and Preface.

Nevertheless, Luther’s practical principles took hold. Worship patterns were codified in church orders and the concept of regional unity cemented in the language of the Lutheran Confessions.20 It wasn’t until the 20th century that some Lutherans were taken up with the idea of “absolute congregational autonomy in all matters liturgical.”21

This article does not suggest or imagine that all the congregations of a 21st century synod adopt a uniform and identical worship practice. Nevertheless, we also cannot ignore how important it was to Luther and the Lutheran confessors that congregations work together in adopting and adapting worship patterns.

Perhaps we can be encouraged that the Livonian problem did resolve. In 1530, only five years after their letter to Luther, their neighbors in Riga (modern-day Latvia) wrote: “So far as is possible and helpful to our people, we may agree not only with the people here in Livonia, but also with our neighbors and other states in the German lands in which the Gospel of Christ is also proclaimed clearly and richly—especially in the principal matters pertaining to outward divine service or ceremonies.”22

Creativity is careful to serve the congregation.

As the busy year of 1525 closed, Luther had nearly completed his worship revision project. The gospel had been carefully taught and translated in words and actions. The tunes had been professionally assessed. But would the Wittenbergers sing? Luther, the pastoral pragmatist, had already worked to ensure that it could be done.

Luther was a musical theologian. He received musical training from a young age, long before he entered the monastery. At the same time that he was learning the Latin chants in school, Luther was learning German folk tunes from his copper-mining father Hans and his mother Grete. He reports that during his early years “his father would relax with a beer and break out into song.”23

This pattern continued in Luther’s own family life. In a famous scene by Gustav Spangenberg, Luther is strumming away, teaching songs to his children from a printed manuscript. Since Spangenberg’s painting is from 1875, some dismiss it as unrealistically idyllic. But this activity would have been common in the Luther household.

Also interesting is the person glancing over Katie’s shoulder. Philip Melancthon was a frequent guest in Luther’s home. But why is he featured in this painting? In my estimation, Spangenberg was portraying an idyll of Lutheran musical pedagogy. Melancthon, the praeceptor Germaniae, represents the idea of Christian education. If the Reformation would endure, it would require musically trained theologians and theologically trained musicians.24

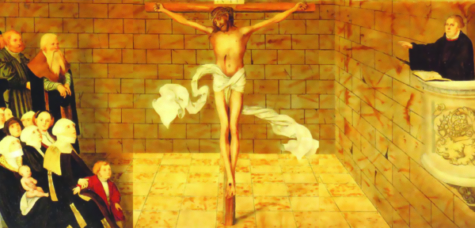

Lower altar panel at St. Mary’s – Lucas Cranach the Younger

How Luther implemented this musical training in Wittenberg isn’t as clear as we might like it to be. One hint comes from another allegorical image from 1547 by Luther’s colleague Lucas Cranach the Younger.

We see the gospel of Jesus at the center, Luther in the pulpit, and the people gathered to listen, pray, and presumably, sing. We notice that men and women are separated into groups (as Luther advised for the communion distribution), but we also notice a congregation of several generations worshiping together. We don’t see a choir, even though we know they used one. How much did the congregation sing? How much did the choir sing? What did a service in 1527 sound like? These questions will remain under debate.25 But if we step back and listen, some key notes emerge.

Luther oversaw publication of a congregational hymnal in Wittenberg. Though the earliest known copy is dated to 1526, evidence suggests that the laity had hymnals in their hands—an Enchiridion—as early as 1524.26

Luther also invited Johann Walter to compose three- to five-part concerted settings of the same hymns listed in the Enchiridion. This Geystliche Gesangk-Buchleyn was also published in 1524.

Luther relied heavily on the scholia (school choir) for modeling the new texts and tunes to the congregation. Students trained in singing during the week were placed centrally among the congregation when the hymn was sung.

With this information, we realize that the two scenes above complement one another while providing a clear picture of how pastor and people worked together in the instruction of hymnody, liturgy, and song—to grow in faith. “For this, one must read, sing, preach, write, and compose. And if it would help matters along, I would have all the bells pealing, and all the organs playing, and have everything ring that can make a sound.”27

The enduring importance of careful creativity.

Ten years after his famous walk to the Castle Church door, the brilliant professor, no longer a bachelor, sat up late one night to compose another document—not to an archbishop but to a good friend. Instead of venting about indulgences, Luther laments medical needs.

“My dear Amsdorf: A hospital has started up in my house. I am very fearful for my Katy, who is close to delivering, for my little Hans has also been sick for three days now and is not eating anything and is doing poorly; they say he’s teething, but they also believe that both are at very high risk.”

The letter to Amsdorf wouldn’t cause the stir of the 95 Theses. The letter’s lasting significance is found only in Luther’s closing salutation: “Written at Wittenberg on the Day of All Saints, in the tenth year after the indulgences had been trampled underfoot, in memory of which we are drinking [Wittenberg beer] at this hour.”28 The date was Tuesday, November 1, 1527. Had it been Sunday or Wednesday, Luther might have been leading worship. Had it been Friday or Saturday, he might have been preparing a sermon or hearing confession. But Luther was commemorating All Saints’ Day with Gemütlichkeit.

Luther provided a pastoral and practical manual for careful creativity.

How much had changed in the previous decade? One need look no further than the All Saints’ Church. The thousands of meaningless private masses had been abolished by the end of 1521. The ten aisles of relics had been removed by 1522. By 1524, the people who had once only stopped to look were now starting to stay and sing, with forms and hymns that they could understand. The results, of course, would be seen and heard far beyond Wittenberg.

Did the brilliant professor realize what he was doing? In 1523, Luther began by revising an old order of service for the sake of the gospel. In 1526, he advised a new order of service for the sake of the gospel. But far from a mere ‘alternative service’ Luther provided a pastoral and practical manual for careful creativity. The wisdom and principles evident in his approach continue to guide pastors and worship planners today.

Written by Mark Tiefel

The picture in the heading is “Luther Making Music in the Circle of his Family” by Gustav Spangenberg.

For full citation information for some notes, see part 1 of this article.

1“Deutsch Evangelisch Messze.” Cf. Leaver, Sings, 84-88.

2 The story is explained in Luther’s “An Exhortation to the Communicants,” LW 53:104.

3 “To translate the Latin text and the Latin tone or notes has my sanction, though it does not sound polished or well done. Both text and notes, accent and melody, and manner of rendering ought to grow out of the true mother tongue and its inflection, otherwise all of it becomes an imitation in the manner of apes.” “Against the Heavenly Prophets” LW 40:141.

4 Leaver, “Deutsche Messe,” 331.

5 The professionals didn’t feel Luther needed much help. Praetorius records a visit by Rupsch and Walter. “Herr Luther had composed the Sanctus in masterly fashion.” Schalk, Paradigms, 27.

6 Lange, Annotated Luther. Cf. LW 53:78

7 Cf. LW 53:127ff and LW 53:153ff

8 Cf. Luther’s Letter to Spalatin (end of 1523), LW 49:68-69, cited in Schalk, Paradigms, 26.

9 Schalk, Paradigms, 51

10 Hoelty-Nickel, Theodore. “Luther and Music” in Luther and Culture, Luther College Press. 1960, 147-148.

11 LW40:141, cited in Leaver, Sings, 86

12 This is not to say that a well-played Irish tin-whistle isn’t proper art! The reference is from Martin Franzmann, Ha! Ha! Among the Trumpets, CPH, 1966/1994, 92 or 96. Cf. Aaron Christie, “Excellence for Christ in All Things,” Worship the Lord #42 (May, 2010).

13 Other reformers, such as John Calvin, would take this approach.

14 This path was advocated by Johannes Brenz. Cf. Elert, Structure, 333.

15 LW 53:47

16 AL 3:139, LW 53:63

17 For a fuller discussion of latitude and limits, cf. page 6 in Stephen Valleskey, “Lutheran Worship Reforms of the 1500s that We Can Still Use Today.” WELS South Central District, January, 2010.

18 “We Germans are a rough, rude, and reckless people, with whom it is hard to do anything, except in cases of dire need.” AL 3:142. What would Luther think of Americans?

19 AL 3:155; LW 53:80

20 By 1580, the pattern of uniform regional church practice had spread throughout Germany. “The confessors were willing to work out their issues of freedom and love for the sake of unity. They saw the exercise of ‘discretion’ … as completely in accord with the very confessions they penned and confessed. They went about exercising that discretion not only by defending it in the confessions, but through active efforts of visitation and through extensive publication of church orders.” Matthew Harrison, “Luther, The Confessions, and Confessors on Liturgical Freedom and Uniformity,” in Chemnitz’s Works, Volume 9: Church Order for Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel. Concordia, 2015, xv-xvi.

21 Harrison, xxi

22 Leaver, “Deutsche Messe,” 333-334

23 Leaver, Sings, 28

24 Cf. Hoelty-Nickel, 149

25 As they currently are. Joseph Herl’s Worship Wars in Early Lutheranism asserts that the choir played the major role, almost to the exclusion of the congregation. Robin Leaver makes the case for a singing laity. Cf. Luther’s Liturgical Music, Fortress, 2017, 209ff and especially Sings, 102ff.

26 Leaver provides an engaging narrative of its development in Sings, 106ff.

27 AL 3:140; LW 53:62

28 The second quote is referenced in Leaver, Church, 2. The first can be found in WA 4:4, #1162.

WORSHIP

Learn about how WELS is assisting congregations by encouraging worship that glorifies God and proclaims Christ’s love.

GIVE A GIFT

WELS Commission on Worship provides resources for individuals and families nationwide. Consider supporting these ministries with your prayers and gifts.

[fbcomments num=”5″]